πίσω

πίσω

COPYRIGHT © by Michaelidou Maria

Dr. Maria Michailidou

SYSTEMIC LUPUS ERYTHEMATOSOUS

Essentials of Diagnosis

- Occurs mainly in young women.

- Rash over areas exposed to sunlight.

- Joint symptoms in 90% of patients. Multiple system involvement.

- Anemia, leukopenia, thrombocytopenia.

- Glomerulonephritis, central nervous system disease, and complications of antiphospholipid antibodies are major sources of disease morbidity.

- Serologic findings: antinuclear antibodies (100%), anti-

native DNA antibodies (approximately two- thirds), and low serum complement levels (particularly during disease flares).

General Considerations

SLE is an inflammatory autoimmune disorder characterized by autoantibodies to nuclear

antigens. It can affect multiple organ systems. Many of its clinical manifestations

are secondary to the trapping of antigen-

The prevalence of SLE is influenced by many factors, including gender, race, and genetic inheritance. About 85% of patients are women. Sex hormones appear to play some role; most cases develop after menarche and before menopause. Among older individuals, the gender distribution is more equal. Race is also a factor, as SLE occurs in 1:1000 white women but in 1:250 black women. Familial occurrence of SLE has been repeatedly documented, and the disorder is concordant in 25–70% of identical twins. If a mother has SLE, her daughters' risks of developing the disease are 1:40 and her sons' risks are 1:250. Aggregation of serologic abnormalities (positive antinuclear antibody) is seen in asymptomatic family members, and the prevalence of other rheumatic diseases is increased among close relatives of patients. The importance of specific genes in SLE is emphasized by the high frequency of certain HLA haplotypes, especially DR2 and DR3, and null complement alleles. Genes that regulate programmed cell death (apoptosis) also appear to be important in the pathogenesis of SLE.

Before making a diagnosis of SLE, it is imperative to ascertain that the condition

has not been induced by a drug (Table 20–8). Procainamide, hydralazine, and isoniazid

are the best-

Four features of drug-

The diagnosis of SLE should be suspected in patients having a multisystem disease

with serologic positivity (eg, antinuclear antibody, false-

Table . Criteria for the classification of SLE. (A patient is classified as having

SLE if any 4 or more of 11 criteria are met.)

1. Malar rash

2. Discoid rash

3. Photosensitivity

4. Oral ulcers

5. Arthritis

6. Serositis

7. Renal disease

a. > 0.5 g/d proteinuria, or—

b. 3+ dipstick proteinuria, or—

c. Cellular casts

8. Neurologic disease

a. Seizures, or—

b. Psychosis (without other cause)

9. Hematologic disorders

a. Hemolytic anemia, or—

b. Leukopenia (< 4000/mcL), or—

c. Lymphopenia (< 1500/mcL), or—

d. Thrombocytopenia (< 100,000/mcL)

10. Immunologic abnormalities

a. Positive LE cell preparation, or—

b. Antibody to native DNA, or—

c. Antibody to Sm, or—

d. False-

11. Positive ANA

Clinical Findings

Symptoms and Signs in systemic lupus erythematosous

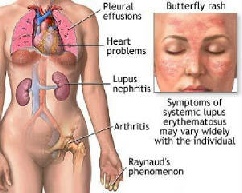

The systemic features include fever, anorexia, malaise, and weight loss. Most patients have skin lesions at some time; the characteristic "butterfly" (malar) rash affects less than half of patients. Other cutaneous manifestations are discoid lupus, typical fingertip lesions, periungual erythema, nail fold infarcts, and splinter hemorrhages. Alopecia is common. Mucous membrane lesions tend to occur during periods of exacerbation. Raynaud's phenomenon, present in about 20% of patients, often antedates other features of the disease.

Joint symptoms, with or without active synovitis, occur in over 90% of patients and are often the earliest manifestation. The arthritis is seldom deforming; erosive changes are almost never noted on radiographs. Subcutaneous nodules are rare.

Ocular manifestations include conjunctivitis, photophobia, transient or permanent

monocular blindness, and blurring of vision. Cotton-

Pleurisy, pleural effusion, bronchopneumonia, and pneumonitis are frequent. Restrictive

lung disease can develop. Alveolar hemorrhage is rare, but potentially life-

The pericardium is affected in the majority of patients. Cardiac failure may result

from myocarditis and hypertension. Cardiac arrhythmias are common. Atypical verrucous

endocarditis of Libman-

Mesenteric vasculitis occasionally occurs in SLE and may closely resemble polyarteritis

nodosa, including the presence of aneurysms in medium-

Neurologic complications of SLE include psychosis, cognitive impairment, seizures, peripheral and cranial neuropathies, transverse myelitis, and strokes. Severe depression and psychosis are sometimes exacerbated by the administration of large doses of corticosteroids. Several forms of glomerulonephritis may occur, including mesangial, focal proliferative, diffuse proliferative, and membranous (see Nephrology). Some patients may also have interstitial nephritis. With appropriate therapy, the survival rate even for patients with serious renal disease (proliferative glomerulonephritis) is favorable, albeit a substantial portion of patients with severe lupus nephritis still eventually require renal replacement therapy.

Laboratory Findings

(Tables 20–10, 20–11, and 19–2.) SLE is characterized by the production of many different

autoantibodies, some of which produce specific laboratory abnormalities (eg, hemolytic

anemia). Antinuclear antibody tests are sensitive but not specific for SLE—ie, they

are positive in virtually all patients with lupus but are positive also in many patients

with nonlupus conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis, various forms of hepatitis,

and interstitial lung disease. Antibodies to double-

Treatment in systemic lupus erythematosous

Patient education and emotional support, as described for rheumatoid arthritis, are especially important for patients with lupus. Since the various manifestations of SLE affect prognosis differently and since SLE activity often waxes and wanes, drug therapy—both the choice of agents and the intensity of their use—must be tailored to match disease severity. Patients with photosensitivity should be cautioned against sun exposure and should apply a protective lotion to the skin while out of doors. Skin lesions often respond to the local administration of corticosteroids. Minor joint symptoms can usually be alleviated by rest and NSAIDs.

Antimalarials (hydroxychloroquine) may be helpful in treating lupus rashes or joint

symptoms that do not respond to NSAIDs. When these are used, the dose should not

exceed 400 mg/d ( 6.5 mg/kg/d), and annual monitoring for retinal changes is recommended.

Drug-

Corticosteroids are required for the control of certain complications. (Systemic

corticosteroids are not usually given for minor arthritis, skin rash, leukopenia,

or the anemia associated with chronic disease.) Glomerulonephritis, hemolytic anemia,

pericarditis or myocarditis, alveolar hemorrhage, central nervous system involvement,

and thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura all require corticosteroid treatment and

often other interventions as well. Forty to 60 mg of oral prednisone is often needed

initially; however, the lowest dose of corticosteroid that controls the condition

should be used. Central nervous system lupus may require higher doses of corticosteroids

than are usually given; however, corticosteroid psychosis may mimic lupus cerebritis,

in which case reduced doses are appropriate. Immunosuppressive agents such as cyclophosphamide,

mycophenolate mofetil, and azathioprine are used in cases resistant to corticosteroids.

Treatment of severe lupus nephritis includes an induction phase and a maintenance

phase. Cyclophosphamide, which improves renal survival but not patient survival,

was for many years the standard treatment for both phases of lupus nephritis. More

recently, mycophenolate mofetil, which may be more effective and is less toxic than

cyclophosphamide, is emerging as the treatment of choice for many patients with lupus

nephritis. Very close follow-